You see, whatever your motivation may be, you will always follow these five broad steps when trying to know something by yourself:

- Knowing what you already know

- Knowing what you want to know

- Trying to know

- Knowing what you do not know

- Actually knowing

The first step is obvious. Whether you actively think about it or not, you will go through some form of initial self-assessment of your needs, motivations, biases, and prior knowledge. The 2nd step is when you choose what your overall goal will really be. It is your first broad strokes that will chart your path of learning objectives. When you actually try to know something (3rd step), we discover how much we really don’t know (4th step). Then we hopefully reach our goal (5th step).

Now, step 4 is actually a very special and important step. It is where your path can split between going back to step 1 (creating a new set of steps), or finally concluding to step 5 (then moving on to the next learning objective). Given this possibility, we can infer this process is both repeating and recursive.

This is what my theory of recursion in self-motivated learning is trying to describe.

Bit of a disclaimer, this article is very empirical and exploratory. If you want a more grounded discussion, get the future book!

Let’s say you want to learn character art. Let us try to categorize our steps through this context.

- Well I know that a character is made of a face, a body, and its pose. (Step 1)

- So, I want to learn body first, then pose. (Step 2)

- I follow a t-pose tutorial. (Step 3)

- I realize that drawing a full body requires that I know how to draw hands, feet, clothes and folds. (Step 4 splits here and goes back to step 1 for the mentioned sub-topics)

- I finally learn how to draw a body. (Step 5 leads back to step 1 for the next topic which is pose)

If you do not know about color theory, or basic drawing techniques, then these sub-topics are further recursions. In fact, in a lot of disciplines, these recursions can go on indefinitely.

This recursive nature is one of the reasons why people get demotivated so quickly when learning a new skill.

Humans rarely do learn linearly. At least when by themselves. Why do you think the phrase “walk before you run” is so popular? The natural human tendency when learning, is to try and skip to whatever we want to do. As such, when we are forced to take detours, we can ‘feel’ as if we are moving farther away instead of closer to our goal. Why do you think this is the case?

In school-assisted learning, this problem does not exist as we just have to be focused on the task-at-hand. We are simply following a plan made by people who know better than we do. But for self-motivated learning, there is nothing stopping us from skipping the necessary ‘recursions.’

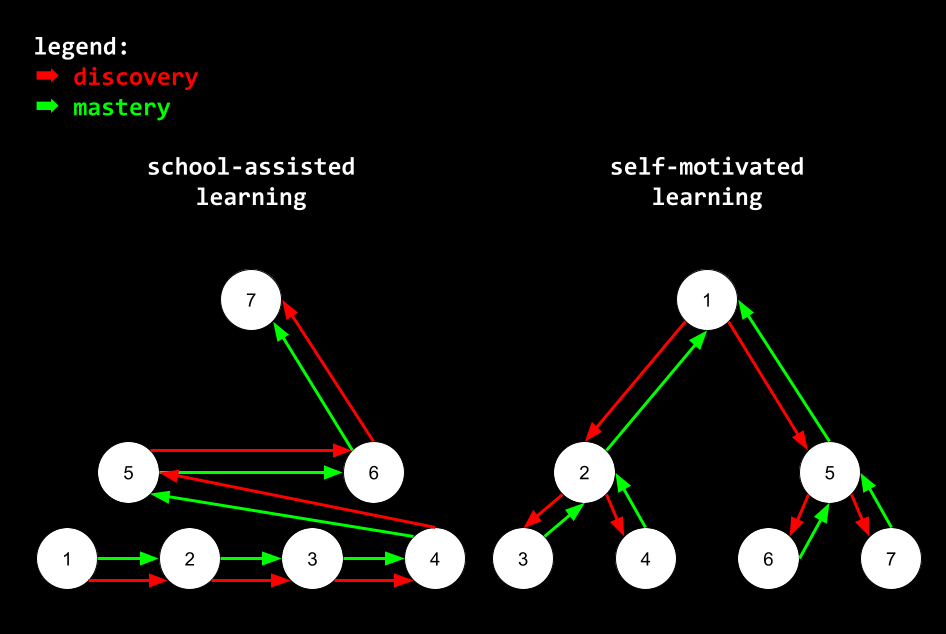

To explore this phenomenon, we can view this theory through a different perspective. Let’s try to compare the difference between school-assisted learning and self-motivated learning through the order in which we traverse a hierarchy of topics.

The most obvious difference that can be seen between the two is the directions of discovery and mastery. In school-assisted learning, discovery and mastery move together. You discover a topic and begin mastering it before you can move on to the next topic. There are exceptions but that’s for a different topic.

On the other hand, when you are teaching yourself, discovery and mastery are in opposite directions. You first discover the top-most topic then gradually discover the sub-topics that it is made up of. It is only when you reach a specific depth that you can truly begin learning.

Just from looking at the graph, you can see that self-motivated learning has a non-linear flow of knowledge acquisition. This is partially why teaching yourself is significantly more difficult. You see, unlike school-assisted learning, our process of discovery and mastery in self-motivated learning does not go one after the other. School-assisted learning excels in delivering content and practicing students in a linear and organized fashion. In a school curriculum, we only have to be worried about one thing at a time. On the other hand, when teaching ourselves, we do not have this luxury. In self-motivated learning, we are overloaded with so many topics at once, what topic do we spend time on first?

Some questions:

Question 1: Is it possible to have our direction of mastery go top-down instead?

No. Mastery implies the mastery of a skill’s components. In Music Production, it is foolish to say that you have mastered Chord Progressions if you have not mastered harmony.

Instead of thinking about mastery as linear, we need to view it as fractional. We can think of it as a pie chart. Our mastery of each component of this skill contributes to our overall partial mastery. Each component can be further broken down as its own pie chart. On top of this, mastery also involves knowing how these different components interact with each other. See the below figure.

It is impossible to say that you have mastered a top-level skill without exploring its low-level skills.

Question 2: How do I know if I have discovered the right depth of recursion for me to start my process of mastery?

The “mental model theory” is a cognitive-constructivist theory. It talks about how all of our understanding revolves on interconnected ideas. When we learn, we are simply trying to connect a new model to our pool of existing knowledge. If a person cannot connect a new model to anything, then they cannot accept it. Even if they try to, it will just result in out-of-context knowledge that they cannot use anywhere.

How does this relate to the question? You see, new expertise is simply just new models. As such, we need to find how we can connect these models to our existing knowledge. If we cannot, then we try to go down one level. Eventually, if we go deep enough, we will find a sub-skill basic enough for us to understand. You will feel it suddenly “click” because you have successfully contextualized something new in your mind.

Finding this ‘baseline‘ for yourself is best done through trials. After each trial, critique yourself to see where you are lacking. Then, stress-learn these areas. If you find more mistakes, then go down more levels.

Note: Stress-learning is a term I use to describe learning a specific narrow sub-skill without moving on to other things.

What now?

When I started learning how to draw characters as a 20-year old programmer, the feeling of frustration definitely creeped up on me. I forced myself to avoid wasting time by doing things I don’t know how to do yet. You see, as self-motivated learners, we are product-centric because we learn top-down. Initially, we only see the top-level skill and want this for ourselves. We fixate on our goal while ignoring the journey.

Humans have the natural tendency to skip learning nuanced information and to go straight into attempting what we want to create.

Then we fail. Then we get demotivated.

However, the theory of recursion tells you that it is necessary for you to fail. It is a required step in discovering the depth you have to go to for you to begin making real progress in learning. Furthermore, we can use this theory as a way to convince ourselves that our improvements in sub-skills matter greatly even if we feel far away from our top-level learning objective.

When I was learning character drawing, I used this theory to convince myself to keep stress-learning the small things because I knew that these small things are the components that are necessary to create stunning art. I am still in the process of doing so today.

I know many people in other disciplines that refuse to go deeper and learn through more recursions because they are afraid to explore their incompetence.

I say this: you’ve already done the hard part and discovered what you are bad at. Now, just stress-learn these and you will come out significantly better at your target skill.

This theory has foundations on the cognitive-constructivist theory of mental models. More on this topic on a future article.

This article is part of a future book entitled, “How to really teach yourself anything.”

Leave a comment