This article is a topic taken from my book entitled “How to really teach yourself programming — for students by a student.”

If we look school, we notice the following possible pattern:

- Junior High School – JavaScript/Visual Basic

- Senior High School – Python

- College 1st year – C

- College 2nd year – C#

While this may not be true for all students, the point still stands — with any curriculum, it is inevitable that for each year, students will be taught a different programming language.

I agree that there can be a strong debate regarding the decision between learning many languages fast or learning a single language deeply. I also agree that there is a balance to be struck between two methods (i.e., having a main language while dabbling in others).

To understand my preference in this decision, I must expound on what I think the benefits of each method will be, as well as their drawbacks.

First, multi-language pedagogy can excel in teaching a student how to speak programming fundamentally. The recently publicized 2022 Harvard CS50 course practices this. They went from Scratch, to C, then to Python. Their rationale behind teaching many languages in a short amount of time is not just for languages’ sake. Rather, it is to ultimately teach students how to teach themselves new languages. It is so that students can learn programming fundamentally. All programming languages operate on the same fundamental ideas (i.e., functions, variables, loops, conditionals, etc.). Therefore, when students move on to attempt to learn another language within 5-10 years, it will only be a matter of looking up the basic building blocks of that programming language. Using multi-language pedagogy can teach students to speak programming itself fundamentally.

You start to ask yourself the same questions:

- Do for loops have the same syntax?

- Are variables declared the same?

- Is there a foreach loop? If not, how do you achieve the same thing?

That said, the same argument can be used for mono-language pedagogy. You see, if students are allowed to have a singular, main language, then more of their knowledge can be used as a deeper basis for when they learn other languages. Multi-language pedagogy fails where mono-language pedagogy excels. Students will be able to ask themselves more complex questions like, “how do I do OOP here?” Or, “is software design here the same as in my main language?”

Furthermore, as mentioned earlier, the student will already have been exposed to many languages that they will be forced to learn (albeit surface-level). This is thanks to school. So, the benefits of multi-language education are already present within the average student, however, to counteract the disadvantages of multi-language pedagogy, the student must have a single, primary language in their own context of self-motivated learning.

When I started programming at 12 years old, I started with JavaScript for web development. At 14, I started my venture in C# and it has been my main language ever since. This meant that a majority of my time in Junior High School was spent learning C#. When I went into Senior High School two years later, the curriculum required me to learn Python. Do note that this was my first time encountering an academic course/subject that was purely about programming. Nonetheless, I excelled in Python effortlessly. I saw Python as a weird version of C#, in fact, I started seeing everything as C#. Then came my first year at college, the curriculum included C programming. That too, I saw as just ‘another C#.’ This was true even in advanced topics like file serialization.

In early 2023, a course required us to code in C. As many may know, C is a low-level language. Which means that C gives you access to the inner workings of how programs work, but it lacks the quality-of-life structures that many higher-level languages have. As mentioned, prior to C, I had already a deep understanding of C# (nearly 5 years experience at the time). The concept of variables, loops, functions, and conditionals were not foreign to me. But what C had that was foreign to me were pointers. Nevertheless, I applied my knowledge of “ref” and “out” keywords in C# to easily understand pointers in C. Furthermore, I thought of pointers as simply classes (because classes were passed by reference, not by value).

There came a time that this college course required us to make a relatively larger machine project which requires more thought into structure. I immediately applied my knowledge in C# regarding scalable code to ensure that I finished the machine project 6 weeks before it was due. Additionally, I applied my knowledge of delegates and namespaces to create my own libraries in C which I could use in all future assignments involving that language.

You see, if I did not have C# as my main language, then I would not have learned its more complex features (i.e., “ref” and “out” keywords, delegates). I would also not have the extensive knowledge of writing code that is scalable for projects (i.e., knowledge of OOP and SOLID). I would not have the same refined thinking skills when it came to complex problems which involved several moving parts. The level of ease I had when tackling C would not be the same if not for the depth I had in C#.

Mono-language pedagogy guides the student when they step into another language. In this way, it can nullify the disadvantages of multi-language pedagogy present in students’ curriculums. With this, I would argue your expertise in one programming language can reflect your expertise in different languages. How can you be taught complex features of a foreign language if you do not understand the same concepts in your own native language?

You then start to ask yourself more complex questions:

- How do you pass by reference here?

- How do you do structs/classes here?

- How do you write files using this language?

- What are the fundamental and standard libraries I need to be aware of that this language has?

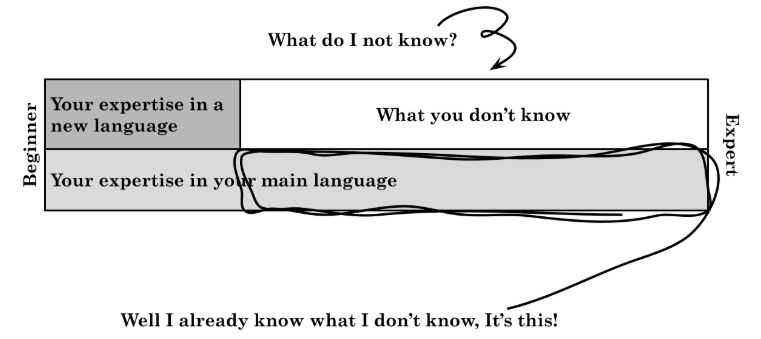

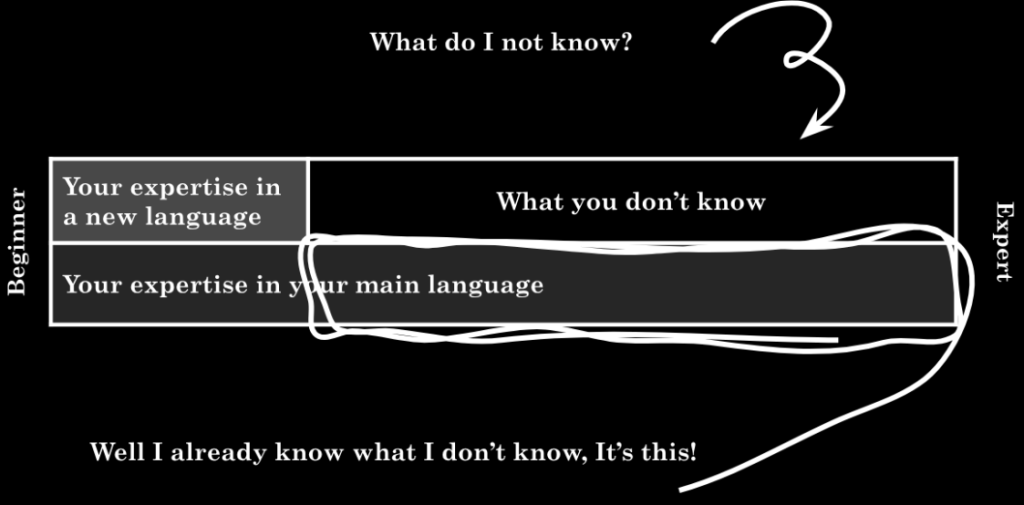

This is a figure I showed in the original seminar. It shows a graph with two bars symbolizing your expertise in your main language, and in a possible new language. Then, it asks the question, “what do I not know?” Subsequently, it answers this question by showing that what you do not know is simply what you already know in your main language.

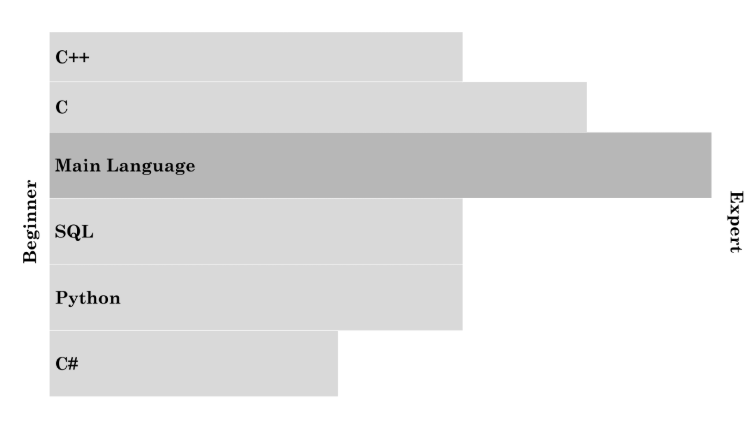

Early on, when I was learning C#, I had stumbled across a very pivotal discovery regarding this language— delegates. The thought of being able to put functions in variables was so revolutionary for me at the time. So revolutionary, that this was the feature I looked for in every single language I put my hands on that was not C#. If a language did have it, great! If a language did not, I would have dedicated ample time into learning how to get the same effect. That was the case with C, as mentioned earlier. As I progressed through college, there had been an increasing number of opportunities that arose where I could use the concept of delegates even in C assignments. Going back, the reason I even learned about this concept in C is because I already knew it in C#. Notice the following graph:

The concept is still the same, if you are trying to learn C# for example, instead of just your main language to assist you, the ideas from C++, C, SQL, and Python will help you fill in that gap of knowledge that you have in C#.

Explore the process of choosing a main-language in my book, “How to really teach yourself programming.”

Leave a comment